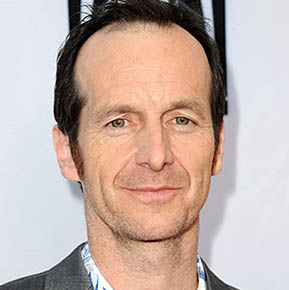

BIPOC Critics Lab writer Alexi Chacón spins a unique interaction with artists Denis O’Hare in Part 1 of his two part interview. In Part 1, Chacón draws on the inspiration of Stud Terkel’s American Dreams: Lost and Found to have himself, O’Hare, and Peterson create individual monologues around citizenship, activism, and democracy.

In What is a Republic, Anyway?, Denis O’Hare and Lisa Peterson skillfully drew parallels between the collapse of the Roman Republic and the stresses being put on by American democracy, leading even the most ardent defenders to leave the show wondering whether the potential for institutional collapse is more fact than fiction. In this play, the primary source is king, as O’Hare’s and Peterson’s carefully researched comparisons leverage ancient texts that detail the fall of the Roman Republic. Audience members take a stab at being historians themselves as they listen to these texts being read out loud and decide for themselves whether these primary sources are indeed a prophecy for the future collapse of American democracy.

At the beginning of the first episode, Peterson describes the theatremaking process, emphasizing that the show’s dialogue was primarily lifted from recorded conversations between her and O’Hare as they conducted research for their other show Song of Rome. I was immediately reminded of verbatim theatre, a genre whose work relies solely on transcribed interviews as the source of dialogue for a show.

Anna Deveare Smith’s Fires In The Mirror is a classic example, being made up of monologues describing the racial tensions leading up to the Crown Heights riot of 1991. The dialogue in that play is directly taken from interviews of Black and Jewish community members.

As a social science researcher, this theatremaking process appeals directly to my love of archival research and my dedication to collecting oral histories. I learned of the insights that oral histories could provide as I interviewed activists in Philadelphia who organized at the beginning of the AIDs epidemic, and in the process their lived experiences revealed details that are often overlooked by history books.

Naturally, I wanted to introduce O’Hare and Peterson to my nerdy obsession with oral histories and together create a piece of verbatim theatre that directly complements the themes discussed in their show. Stud Terkel’s American Dreams: Lost and Found served as the perfect introduction. The book itself is a collection of oral histories that debate the validity of the American Dream. From this collection, I chose Mary Lou Wolff’s interview for us to read. In her interview, Wolff describes a social awakening as she grows into the role of an organizer who enacts local change in her community.

As we read through the oral history, each of us independently highlighted passages that discussed Wolff’s notions of citizenship, activism and democracy. Afterwards, we each stitched these pieces of dialogue into a coherent monologue that could be performed.

The following 3 monologues are the end product of our theatrical exercise.

Denis O’Hare:

We had history in school. I always felt a little uneasy with it.

I thought that was just for high-class people. I just felt foreign. I’d see some of the suits Abraham Lincoln wore or something. But I remember just feeling ill at ease. The words “democracy” and “government,” they just reminded me of school and the nuns giving lessons.

I went to work at the headquarters of the Young Christian Students. I edited a magazine for working women. I had a very small salary. Finally, I gave all that up and got married. I was twenty.

I had nine children. It was absolutely full-time. Once in a while somebody would remember and say: “Could you come and give a speech?” I’d always say: “No, I’m a mother, I’m too busy.” Sometimes I’d spend hours in a rocking chair with a baby, looking at him and wondering what was going on.

My husband made an effort to try and understand what it was I was talking about. Often, he would throw up his hands and say: “Mary Lou, I don’t know what you’re talking about. What is it you want to talk about? Do you want to go out and buy a new dress?”

Then another little bunch of women said: “Why don’t we have a Great Books discussion class?” We all laughed. No people in this neighborhood would be interested. This is not that kind of a neighborhood. Within a few weeks, we had a Great Books discussion class made up of just the regular working-class people. One of the first ones we read is the Declaration of Independence. We spent three hours discussing the first half of the first sentence. This is the first time I, as an adult, ever discussed with other adults what the Declaration of Independence could possibly mean to me. There were intelligent people thinking about the same kind of things that we were thinking about.

Every once in a while I’d pick up a newspaper and read about CAP, Campaign Against Pollution. Father Dubi was the young priest at the head of it. They broke rules. They carried on a fight against Commonwealth Edison and finally won an anti pollution ordinance. They went into other issues and changed their name to Citizens Action Program.

It was on a Sunday afternoon. A whole new thing happened. We went to the alderman’s office. Father Dubi was our spokesman. There wasn’t room in the office, Alder man Pucinski said, so he’d come out. Pucinski said: “I’ll just stand on top of this car here and talk.” He took the microphone away from Father Dubi and climbed on the car. Father Dubi pulled the microphone away from him: “This is our microphone, we’re using it.” I was stunned. I couldn’t believe this. A priest pulling a microphone away from an alderman.

We never saw anything like this before. After it was over, the crowd lingered around. Pucinski came out again and Len said: “Are you sure you don’t have any financial holdings?” Pucinski got mad and said: “If you weren’t a priest, I’d punch you right in the nose.” Father Dubi pulled his collar off and said: “Go ahead and punch, try it.”

I thought it was great. It was connected with my impatience about too much talk. I began to realize I liked direct action. Not only was it more exciting, but it was a glimmering of the idea that you don’t get anywhere if you talk too much. At some point, you must act.

Action. The word came into my vocabulary.

Here, suddenly, was a group of people I liked, admired, saying: “You don’t have to always be polite.” This was a complete shock. That’s something you’re taught from the time you’re a baby. If you want to get anywhere, you have to be polite. Follow the rules. If officials say, “Sit down and wait,” you sit down and wait.

I began to think there are rules made by some people, and the purpose of those rules is not really order. The purpose is to keep you in your place. It may be your duty to break some of those rules.

I liked it, I enjoyed it

I was always a very quiet, polite person. If I had to speak in front of anybody, my face would flush. I would get embarrassed. But the people from CAP seemed to see something different in me. They began to treat me in a way that I wasn’t even treating myself. They expected me to do things I never thought I could do. Maybe I was different than I thought I was.

From that moment on, I began to think it was possible, though difficult, to have a democracy. It was an experiment, risky, chancy. But you couldn’t say: “Okay, we got a democracy.” It’s an ongoing process that has to be carried on with each generation.

I don’t like the word “dream.” I don’t even want to specify it was American. What I’m beginning to understand is there’s a human possibility. There are many, many possible things people can do personally. There are many possible things people can do publicly, politically.

How do you make them come together? That’s where all the excitement is. If you can be part of that, then you’re aware and alive. That for me is the dream.

We had history in school. I always felt a little uneasy with it.

The words “democracy” and “government,” they just reminded me of school and the nuns giving lessons. As if what they were telling about was musty and had nothing to do with living on Chicago Avenue.

I went to a Catholic girls’ college for a year. It was not upper-middle-class, but I thought it was.

I had romantic ideas. I don’t know why I thought to be a worker, to work in a factory, was the best thing of all. Now I think it’s crazy. I wish I’d stayed in that college.

After a series of these crazy jobs, I went to work at the headquarters of the Young Christian Students. I edited a magazine for working women. I had a very small salary. Finally, I gave all that up and got married. I was twenty.

I had nine children. It was absolutely full-time. Once in a while somebody would remember and say: “Could you come and give a speech?” I’d always say: “No, I’m a mother, I’m too busy.” Sometimes I’d spend hours in a rocking chair with a baby, looking at him and wondering what was going on.

I spent a lot of time reading, though not in any disciplined way. I’d just pick up a book here, sometimes it would be a classic, but I’d find myself wishing there were somebody around I could talk about the book with. There was nobody.

A new young priest came to our parish. I said to him: “So much of the church is concerned with the education of kids. We adults right now are not certain of so many questions and upheavals and changes. Why don’t you have something for us where we could sit and discuss?

After a few weeks, lo and behold, I don’t know where he found these people. They lived in the neighborhood for years, and I never knew any of ’em. We came together in the basement of the rectory. It was a shock to me to find out they were all saying: “Yes, we have felt isolated. We had nobody to discuss any of these things with. We’d sure like to talk about some of the changes.”

We decided to start an organization.

Dolores came up with a good idea. She made a sign for every dead tree in the whole area: This is a Dead Tree. It Should Be Cut Down. It made fun of the officials because they were always cuttin’ down trees in front of people’s houses, but they were the wrong trees. We had two hundred twenty-five signs up. Within a few days, all those trees were cut down. We learned our first lesson: calling attention, making fun of officials, and going over the head of the alderman.

There was another dramatic issue: a street that was made a speedway when they built the Kennedy Expressway. It was a neighborhood side street that became dangerous. For years we were trying to get stoplights. Nothing happened. There was a motorcycle accident. Two kids were killed. We visited every house, and the response was overwhelming. Three or four hundred people came to our first meeting. We started our organization.

I began to realize I liked direct action. Not only was it more exciting, but it was a glimmering of the idea that you don’t get anywhere if you talk too much. At some point, you must act.

Action. The word came into my vocabulary.

I began to think there are rules made by some people, and the purpose of those rules is not really order. The purpose is to keep you in your place. It may be your duty to break some of those rules. I liked it, I enjoyed it.

I was always a very quiet, polite person. If I had to speak in front of anybody, my face would flush. I would get embarrassed. But the people from CAP seemed to see something different in me. They began to treat me in a way that I wasn’t even treating myself. They expected me to do things I never thought I could do. Maybe I was different than I thought I was.

People were saying that I’m an organizer. I didn’t know exactly what an organizer did. I thought of them as mysterious people. Later I found there was nothing mysterious about them. It was just the work they did.

They were gonna have a meeting at McCormick Place, about five or six hundred people. We need somebody for a keynote speaker, somebody who’s gonna turn the crowd on. I was wondering who they were gonna get. Father Dubi said: “I propose we have Mary Lou.” I was absolutely stunned. My past reaction would have been to say: “Oh, no, I don’t think I can do it.” But now I thought: If they think I can do it, though it scares me, I’ll try. So I went home and wrote my speech myself. The day came, lo and behold, I got up and I knew it was a good speech ’cause the crowd was reacting.

At the end, I said—it was a little corny—any time there’s a gathering like this, of people coming together and deciding they have to fight, if Jefferson or those people are around anywhere, they must be thrilled, they must be saying: This is what we had in mind.

From that moment on, I began to think it was possible, though difficult, to have a democracy. It was an experiment, risky, chancy. But you couldn’t say: “Okay, we got a democracy.” It’s an ongoing process that has to be carried on with each generation. All that occurred to me as I was writing the speech. I’ve done more reading and thinking about it since. And I know that’s right It was the first time I realized what that was about.

The words “democracy” and “government,” they just reminded me of school and the nuns giving lessons.

Yet I knew things were happening to me.

I began to think there are rules made by some people, and the purpose of those rules is not really order. The purpose is to keep you in your place.

People were saying that I’m an organizer. I didn’t know exactly what an organizer did. I thought of them as mysterious people. Later I found there was nothing mysterious about them.

From that moment on, I began to think it was possible, though difficult, to have a democracy. It was an experiment, risky, chancy. But you couldn’t say: “Okay, we got a democracy.” It’s an ongoing process that has to be carried on with each generation.

What I’m beginning to understand is there’s a human possibility.

Certainly circumstances have to come together. How do you make them come together?

Explore more

Categories: 2020/21 Season. Tags: Denis O’Hare, Lisa Peterson, and What the Hell is a Republic Anyway.

My Cart

My Cart My Account

My Account Gift Certificates

Gift Certificates Find Us

Find Us